On Friday, April 29, 2005, Wesley Triplett and Jan Stackhouse left New York City for a weekend in the Berkshires, where Wesley owned a second home in the quiet town of Stockbridge, Massachusetts.

The trip was one of grief and healing: in early April, Wesley had lost his longtime partner to lymphoma, and Jan, one of Wesley’s closest friends, accompanied him to a familiar place offering solace and escape from the city’s relentless hum.

Jan and Wesley spent the weekend enjoying the crisp April air and colorful blooms of early spring in Western Massachusetts. The landscape blossomed against the backdrop of large oak trees while thin, meandering creeks fed into the peaceful Housatonic River.

Just down the street from Wesley’s home stood the Norman Rockwell Museum, the artist’s former studio that now displayed his signature, idealized visions of small-town America. Wesley’s home in the Berkshires, by all accounts, embodied the same tranquility.

On Sunday afternoon, 52-year-old Jan told Wesley she was heading out for a walk before they returned to the city. She pulled on a sweatshirt, laced her running shoes, and left Wesley’s home on Christian Hill Road around 1 p.m.

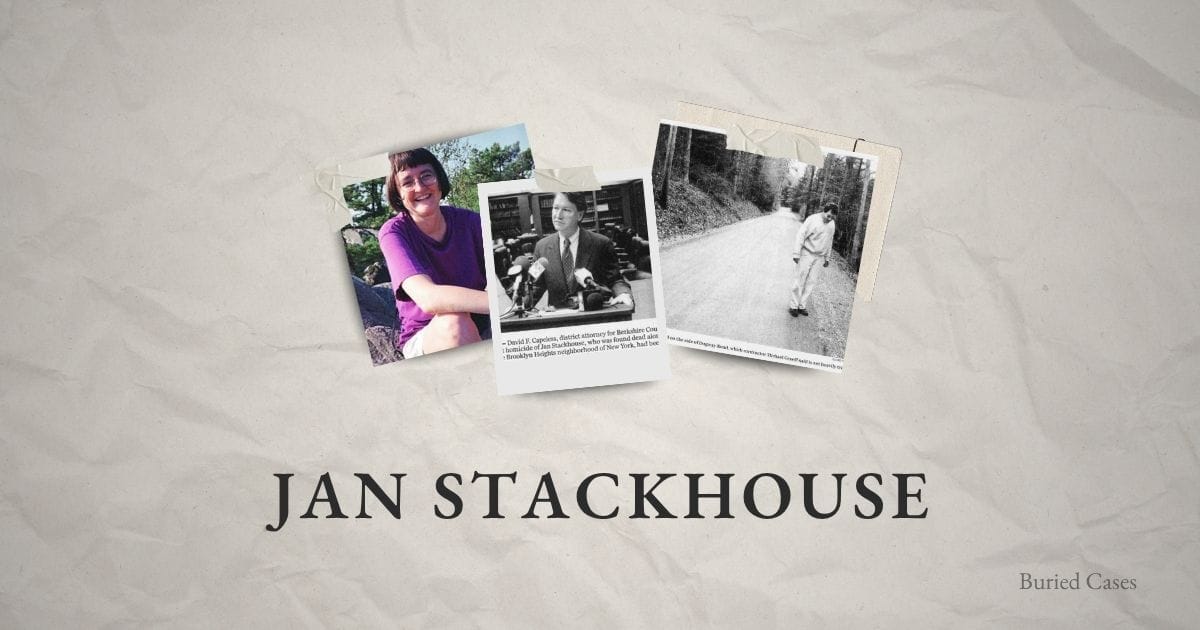

Jan Stackhouse. Source: janstackhouse.org

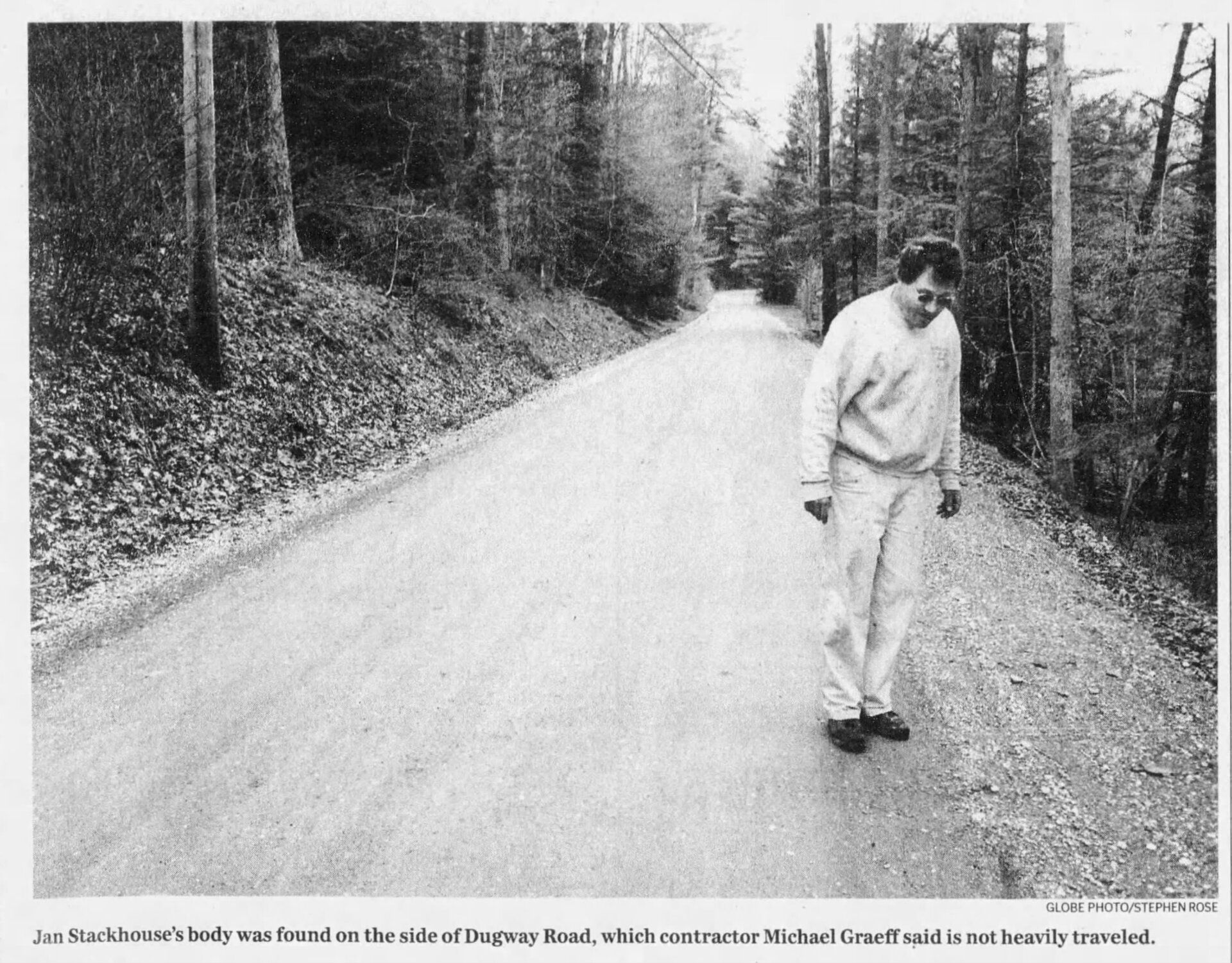

Thirty minutes later, a motorist driving along Dugway Road, less than a mile west of Wesley’s home, noticed something strange and out of place on the country lane’s narrow shoulder. A body lay motionless in the gravel, blood darkening the ground beneath it.

The driver quickly dialed 911, but poor cell service forced him to one of the nearest homes, where he called for help. When Stockbridge police arrived at the scene near the intersection of Dugway Road and Route 183, they confirmed what seemed unthinkable.

In the brief window of time between leaving Wesley’s house and being spotted by the passing motorist, Jan Stackhouse had been killed and left on the roadside.

Daily News (New York), May 3, 2005

Just east of where Jan lay, Mohawk Brook wound through the trees before emptying into the Housatonic River south of 183. It was an idyllic setting most days, but on this Sunday, the first day of May, it became a wholly unexpected crime scene.

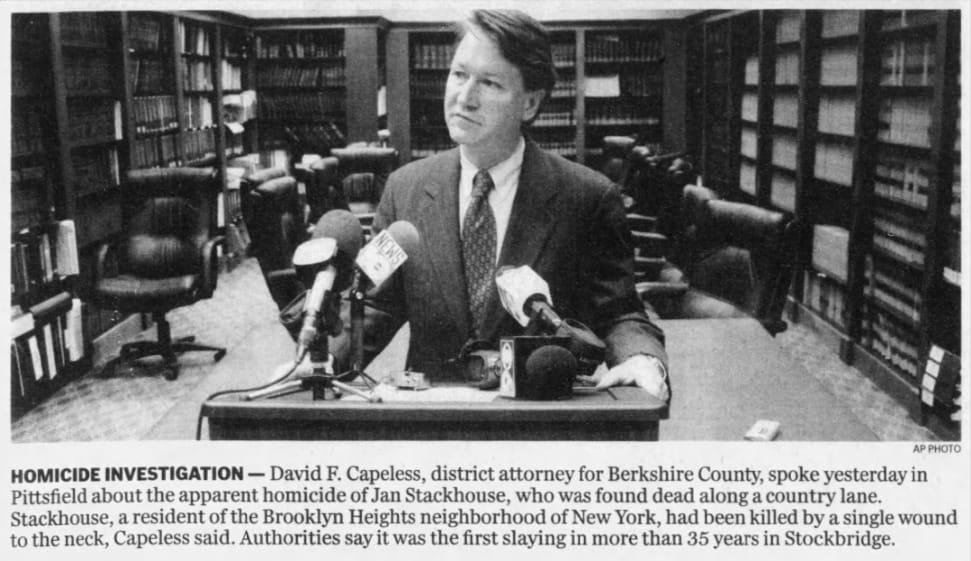

Stockbridge hadn’t seen a homicide in 35 years—not since 1969, when local John Winn beat a man to death after the man had allegedly assaulted Winn’s daughter.

Stockbridge Police Chief Richard Wilcox and his officers secured the scene and canvassed the quiet neighborhood. The initial investigation revealed that Jan had died from a single wound to the neck, but Wilcox refused to say whether a weapon had been recovered or how exactly Jan had been injured. If police knew the mechanism of her death, they kept it well-hidden from the public.

That Sunday, local and state police swept through the area with search dogs and metal detectors, working the banks of Mohawk Brook and the graveled shoulders of Dugway Road. Investigators kept returning to the same perplexing question: how could someone kill Jan Stackhouse in broad daylight on a small country road in less than 30 minutes, right down the street from a friend’s house?

The answers wouldn’t come quickly. As days turned to weeks, rumors began threading through hushed conversations: theories whispered over coffee, speculation that grew more alarming the longer police remained silent.

Jan Stackhouse was born on July 10, 1952, in Montevideo, Uruguay, the daughter of American diplomats with the U.S. Foreign Service. Their work carried the family across the world, allowing Jan to live in places like Lebanon and Libya as a child. She spent time in Washington, D.C. and Israel, where she attended high school.

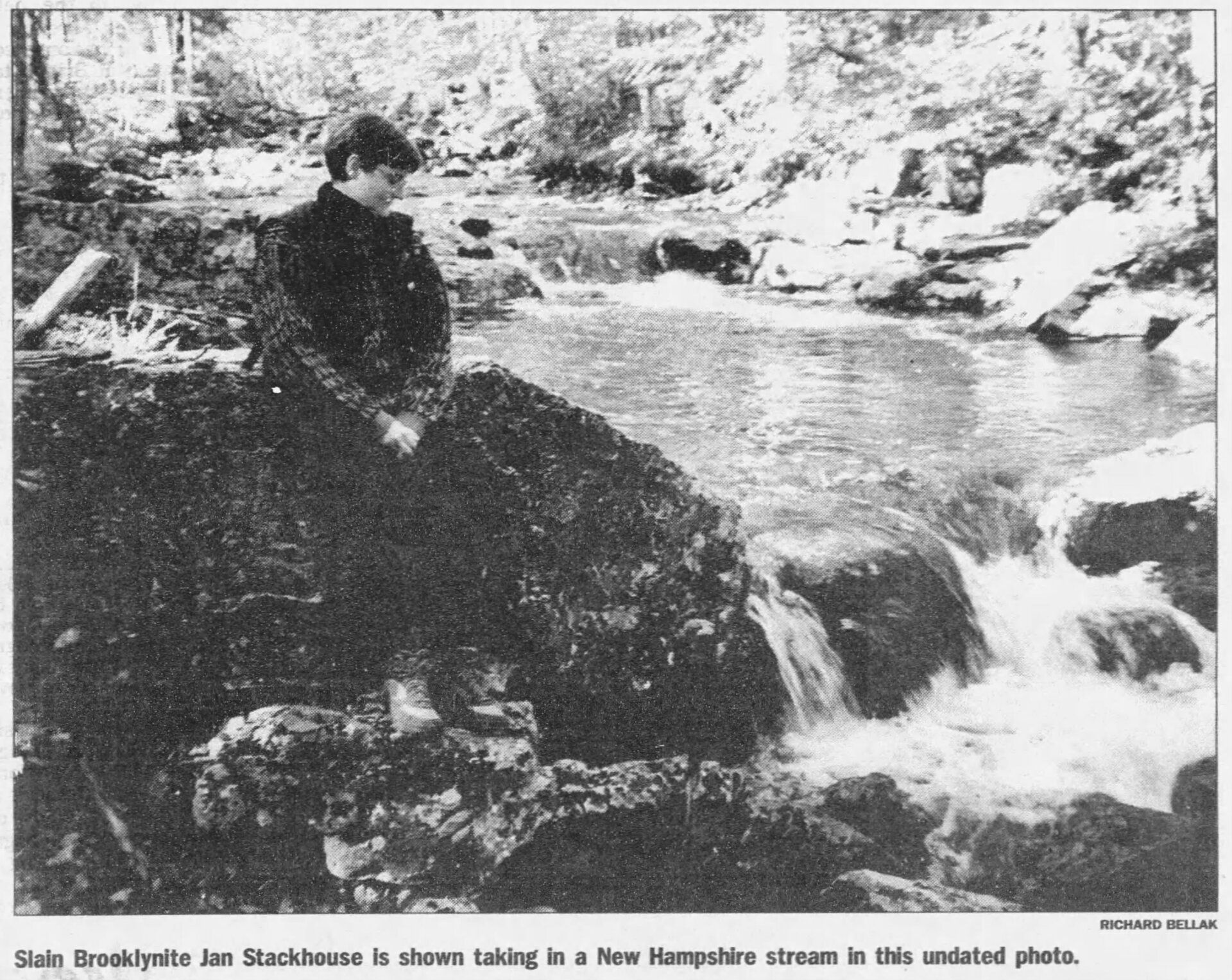

As an adult, Jan had built a life in Brooklyn Heights, where she lived in a five-story brownstone on Brooklyn’s Remsen Street. Neighbors described her as smart, “culturally and politically intense,” and “very much into women’s rights, workers’ rights,” said one neighbor, 71-year-old Richard Bellak. She often filled her apartment with the sounds of Thelonious Monk and Charlie Mingus.

She lived alone—divorced once, with no children—but her life was far from solitary. Jan managed the business operations for Service Employees International Union Local 1199, a union representing hospital and health care workers. She had spent most of her adult life working toward justice for women and workers, starting when she helped unionize the Yale bookstore in 1975.

From then on, Jan dedicated her life to helping others protect and retain their rights. She co-authored Brass Valley: The Story of Working People’s Lives and Struggles in an American Industrial Region, an in-depth, academic review of the history of laborers in Western Connecticut’s Naugatuck River Valley.

Jan made it her mission, as her biographical website put it, to “bring economic, political and social justice to the lives of workers and women.” She had dedicated her life to the freedoms of others, and in just one short window while on a quiet country walk, Jan was gone.

The Boston Globe, May 4, 2005

Right away, state and local authorities questioned residents on Dugway Road, speaking with anyone who might have seen or heard something around the time Jan was found. No one had.

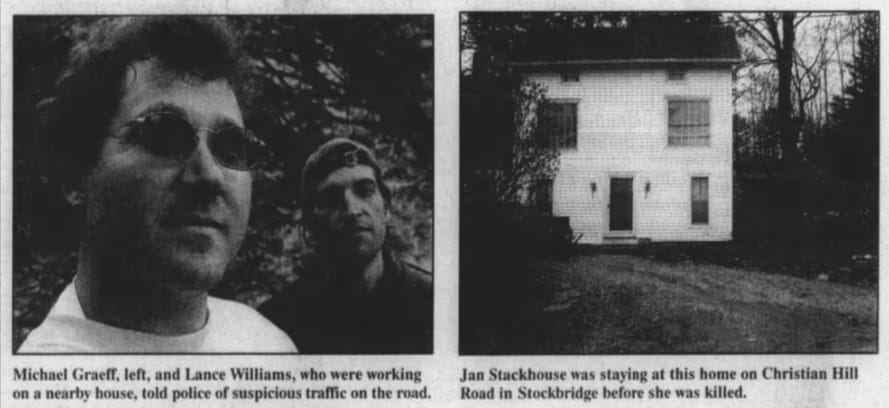

The stretch of road where Jan died was visible from only a handful of homes, and none of those residents had been looking out their windows, or home, at the right moment. The closest house belonged to Alexandria Swann, 51, who said she wasn’t home when Jan’s death occurred.

Her boyfriend, Lance Williams, had been there working on household projects, though. In the days leading up to Sunday, Williams said, he’d noticed something odd: unfamiliar vehicles—a white truck, a dark green SUV—cruising past the house more frequently than usual traffic did. He thought it odd enough to mention to a friend at the time, and reported these vehicles to police when interviewed.

Details about what exactly happened to Jan were sparse. A source close to the investigation said of the roadside scene, “there was blood everywhere.” Days after the initial cleanup, blood still marked a number of leaves near a fallen log.

When she was found, Jan was fully clothed in the sweatshirt, blue jeans, and running shoes she had worn on her walk. It was believed that she hadn’t been killed during an attempted sexual assault.

As police spoke with neighbors, they learned that traffic in the area had increased in recent weeks, but aside from Williams’ observation, there wasn’t much out of the ordinary in the time leading up to Jan’s death.

The Boston Globe, May 3, 2005

Within days, New York City detectives joined the investigation. Their involvement was obvious: had someone followed Jan from Brooklyn? Was her death connected to her decades of labor organization efforts? Union work often made enemies, as management didn’t appreciate workers who knew how to preserve, or expand, their rights.

But despite Jan’s many years of work and reputation for persistence, authorities believed she had few, if any, enemies. She did have plenty of supporters, however. Jan’s union soon put out a reward of up to $10,000 for information leading to an arrest in her case.

Those familiar with Jan’s line of work in New York City noted an interesting detail. Her death on May 1 coincided with International Workers Day, a designation honoring laborers worldwide since 1889.

Back in Stockbridge, the theory that Jan’s murder was the result of a disgruntled labor dispute gained traction—if only as a way for locals to believe that crimes like that didn’t happen in their community. For some residents, it was reassuring to think that violence followed Jan from the city than to accept that it had been waiting in Stockbridge all along.

But after searching Jan’s home and questioning her neighbors and colleagues, police found no reason to believe her death was related to her work. Authorities in both states still had no definitive answers the week of her death, but the hired-hit scenario didn’t hold up under scrutiny.

By the following weekend, Stockbridge police ramped up their activity in the area, setting up checkpoints along Route 183 and Dugway Road. They asked passersby how often they came through the area and if they had noticed anything unusual in prior weeks. The additional police force may have helped Stockbridge residents feel safer, but it didn’t generate any leads in Jan’s case.

The Berkshire Eagle, May 4, 2005

Stockbridge was noticeably on edge by mid-May. Some locals believed a killer walked among them, while others were simply disquieted by the fact that police had so few leads.

With residents questioning the police’s progress and feeling unsafe in their own homes, authorities called for a community meeting to be held at the Austen Riggs Center, where residents could ask questions and police could address their concerns in a communal setting.

A town meeting would be ideal, noted one psychiatrist on Main Street, as “a careful, thorough and confidential police investigation has left townspeople with little information and no way to calm their anxieties over the recent death of Jan Stackhouse.”

More than 60 residents attended the meeting, which seemed to alleviate the town’s shared anxieties. It was an opportunity for locals to voice fears, hear directly from town officials, and to feel less alone in their collective uncertainty.

During the meeting, it was agreed that the town of Stockbridge would write condolence letters to the family of Jan Stackhouse and to Wesley Triplett, who had now lost, in the span of one month, a longtime partner and a close friend. More than 140 residents signed Jan’s letter in the days that followed. Despite the meeting’s positive outlook, Police Chief Wilcox was unable to provide progress on the case.

“I wish I could stand up there and say that we have something,” Wilcox said. “But I can’t.”

The Berkshire Eagle, May 25, 2005

After the meeting, police again increased their presence around town, and in June, another meeting was held to approve overtime pay for the strained police force.

The investigation into Jan’s death had been a procedural challenge, to be sure, but it was also an expensive one. The town meeting ensured that funds from Stockbridge’s accounts would cover whatever police needed to keep the town safe—and to solve Jan’s case.

Throughout the investigation, Police Chief Wilcox emphasized that Jan’s death was still considered a homicide, and not yet a murder. Homicide, Wilcox reminded residents, could be accidental, while murder required premeditation and intent. He cautioned the community against assuming Jan was murdered, and acknowledged that police needed more information before they could make a final determination.

As the summer of 2005 wore on, Jan’s death remained a mystery. Wesley Triplett had been ruled out as a suspect, and police believed Jan’s death wasn’t the result of a serial killer in the area. Back in New York, Jan’s friends and colleagues held a gathering in July to celebrate what would have been her birthday, and to honor a life cut far too short.

State and local police continued to explore leads and revisit the crime scene on Dugway Road. With no clear answers, residents formed their own stories about what happened on Sunday, May 1, 2005.

“The problem with this process is that with very little information, people do all kinds of speculation and gossip,” said Police Chief Wilcox.

Whatever rose-colored image Stockbridge had constructed of itself as the tranquil home of Norman Rockwell and all-American pastimes was, for the time, shattered.

Through the fall and winter of 2005, the town lived in unease, with residents questioning those who would normally be above suspicion. One unsubstantiated rumor considered Alexandria Swann’s boyfriend, Lance Williams, a suspect because he had been working on the house nearest to where Jan’s body had been found.

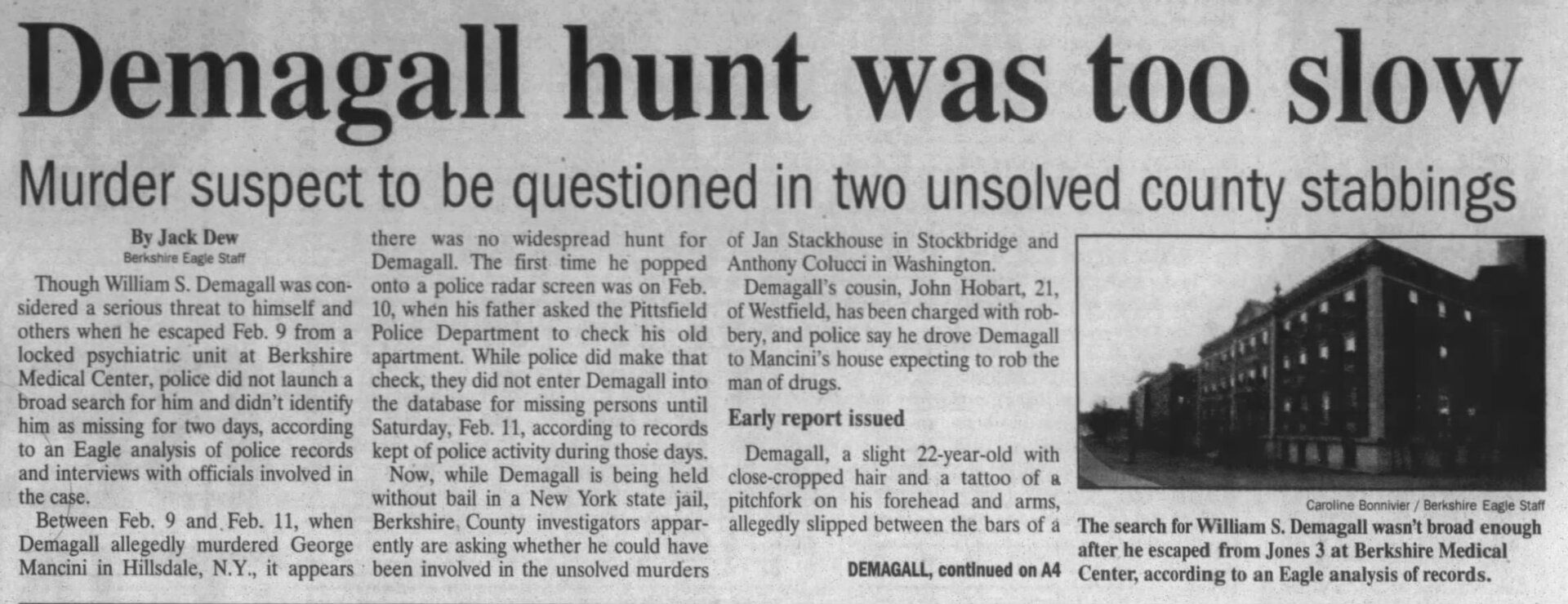

In early 2006, a more unsettling rumor began to circulate. That February, 22-year-old William Demagall—described as a “transient” and survivalist in the Berkshires region—escaped from a psychiatric unit at Berkshire Medical Center in Pittsfield, 30 minutes north of Stockbridge.

Within two days, he’d traveled to Hillsdale, New York, where he murdered George Mancini, a 56-year-old retired schoolteacher. Demagall stabbed and bludgeoned Mancini, then set his house on fire in an attempt to destroy the evidence.

When he was caught, Demagall confessed that he had been living outside, in caves scattered throughout the Berkshires. One of Demagall’s supposed shelters was located one mile from where Jan’s body was found.

The Berkshire Eagle, February 26, 2006

There had also been an another murder in the region just two months after Jan was found dead. On July 4, 2005, Anthony Colucci went missing in Pittsfield. His body turned up days later, stabbed multiple times.

Investigators questioned Demagall about Jan and Anthony, and his whereabouts throughout 2005, before being held at Pittsfield’s hospital. Demagall’s father, Steven, insisted his son couldn’t have been responsible for the murders because William had been living at home then.

“He wasn’t manic then and he wasn’t psychotic,” Steven told reporters, “and when he did become manic, he wasn’t as psychotic as he is now.”

Despite the geographic proximity and the fact that both unsolved Berkshires murders involved stabbings, investigators never conclusively linked Demagall to the deaths of Jan or Anthony.

He was eventually convicted of second-degree murder for killing George Mancini and sentenced to twenty-five years to life. It took four separate trials to establish that he was mentally competent and understood his actions during the crime.

With Demagall ruled out, Jan’s case went cold once again.

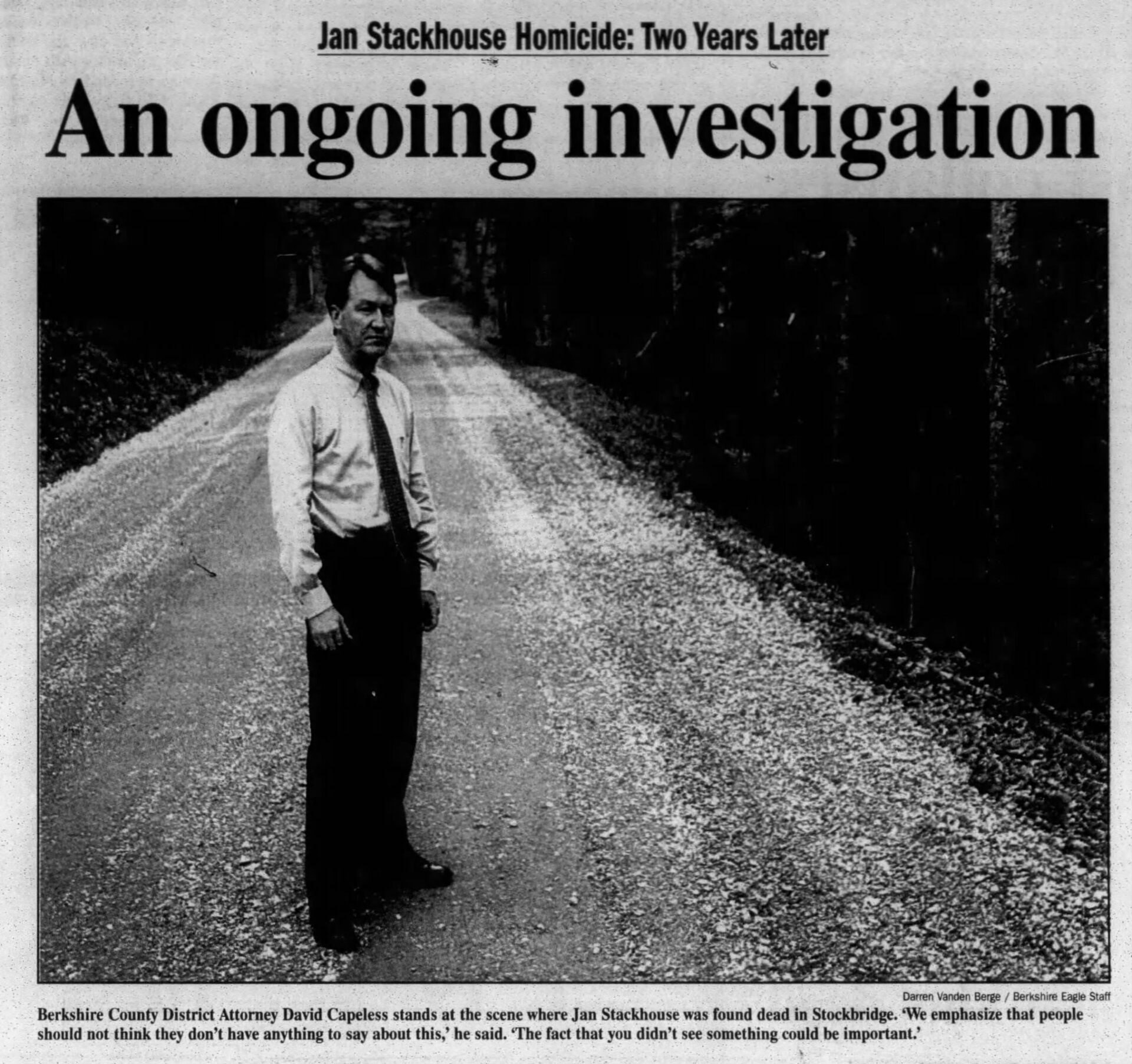

The Berkshire Eagle, April 30, 2007

By May 2007, the case remained unsolved. When The Berkshire Eagle surveyed Stockbridge residents that month, 46% believed the mystery of Jan’s death would continue, while 43% thought no one would ever be charged in her death. Only 11% felt the perpetrator would eventually be caught.

In May 2020, 15 years after Jan’s death, journalist Carole Owens presented an intriguing theory about what could have happened on Dugway Road—one that had quietly circulated for years.

Owens suggested, in The Berkshire Edge, that a truck speeding down the road—its driver distracted or inattentive—could have clipped Jan as she enjoyed her Sunday afternoon walk before returning to Brooklyn. The theory could account for the vague details about Jan’s neck wound, and the narrow time frame in which she died.

“If Stackhouse were walking facing traffic as recommended along country roads, she would be on the passenger side of the vehicle,” Owens wrote. “What if an extended truck mirror gashed her neck and the driver never realized it? Is that what happened? No way to prove it.”

Others, like cold case expert Sarah Stein, believed Jan’s death was “a crime of opportunity,” a matter of Jan being in the wrong place at the wrong moment, visible and vulnerable to someone who happened to pass by.

“I don’t think there’s any personal connection between the killer and the victim,” Stein said. “There’s no evidence of overkill, or passion, or anything of that nature. I think it was just a case of being at the wrong place at the wrong time.”

In 2014, Police Chief Richard Wilcox retired after nearly a decade of living with Jan’s unsolved case. He called her death “a very big frustration ... in terms of my ability to give the community peace of mind.” His replacement, Robert Eaton Jr., arrived hoping to bring fresh eyes and new answers. But Eaton’s tenure came and went, and Jan’s case remained unsolved.

Current Police Chief Darrell Fennelly replaced Eaton in May 2016. Today, local and state investigators remain committed to Jan’s case, hoping that new leads, witnesses, or evidence emerge from the pastoral landscapes and streets of Stockbridge.

• • •