On Christmas Eve 2002, New Mexico state police warned holiday drivers to avoid the southeastern region of the state if possible. Severe winter conditions and icy roads had made it unsafe to travel through Chaves County, including Roswell, and Eddy County, home to Carlsbad.

Recently, Carlsbad’s daytime temperatures had been pleasant, climbing into the 40s, but nighttime lows often dropped into the 20s, and whatever moisture was in the air froze and clung to the roads by morning.

Around 7:45 a.m. on Christmas Day, under a gray winter sky, a driver heading east out of town and passing an alfalfa field noticed something out of place—something that clearly didn’t belong in such an otherwise vast, ordinary expanse.

Near the intersection of Thomason Road and Fiesta Drive, the driver saw what appeared to be a person, but why they would be in such a field, at this time and on Christmas Day, was unknown. The driver pulled over and dialed 911.

When Carlsbad Fire Department arrived on the scene, first responders found a young woman barely clinging to life. She shivered violently and appeared to be suffering from massive head wounds.

Potential hypothermia and physical trauma had pushed the woman to the brink of unconsciousness. She was rushed to Carlsbad Medical Center, but when the extent of her injuries became clearer, the woman was airlifted to Covenant Medical Center in Lubbock, Texas, 180 miles to the northeast.

There, doctors waited for her body temperature to regulate so she could undergo surgery. During the operation, they removed several fragments of bullets from her skull. By the following day, the woman was in a coma and considered to be in extremely critical condition.

Back in Carlsbad, Eddy County Sheriff’s Department investigators canvassed the alfalfa field and surrounding area for clues as to what may have happened to the woman. Based on her condition—the hypothermia, the rigor in her limbs—authorities believed she’d been lying there for hours, possibly since the night before.

After questioning residents and businesses in the vicinity, investigators learned that the woman had last been seen around 10 p.m. at Allsup’s, a convenience store not far from where she was found.

There, authorities located her car, with the driver’s side door open and her keys still inside. It wasn’t immediately clear if the woman had been taken against her will or freely, but in either case, she had left the vehicle in a hurry.

Throughout Christmas Day, Eddy County Sheriff Kent Waller and Lt. Jim Ballard collected and processed what little evidence they could find. Most of it, however, came from the woman’s surgery: they hoped that the bullet fragments might indicate what firearm had been used in the crime.

On the morning of December 29, four days after she was discovered in the field, the young woman died from her irreparable wounds. Despite surgery and around-the-clock medical care, she could not be saved.

The woman was 21 years old, and her name was Sasha Hedgecock.

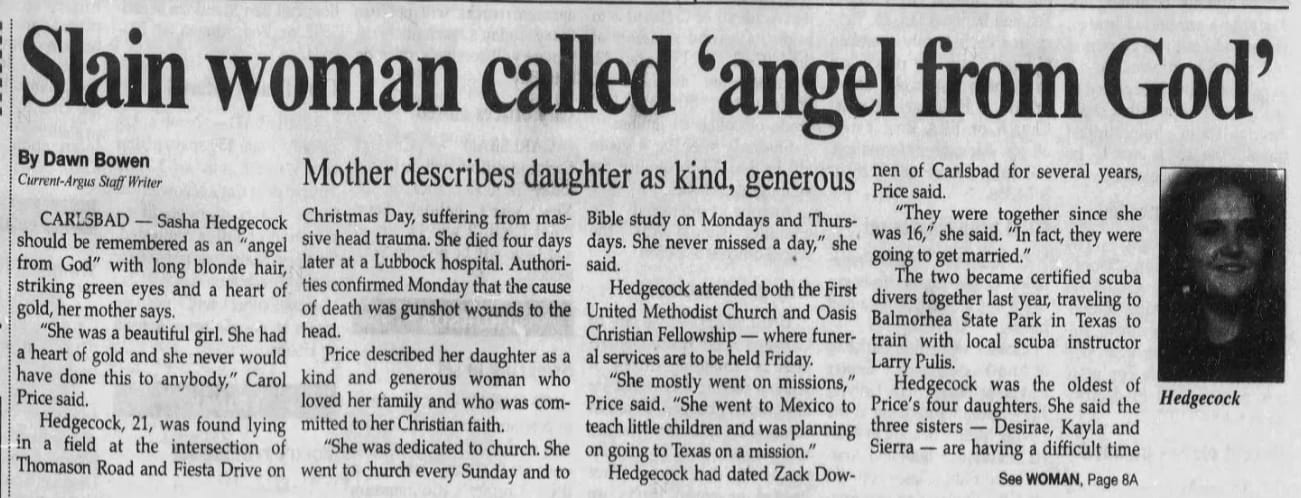

Carol Price described her blond-haired, green-eyed daughter as an “angel of God,” a bright, kind churchgoing young woman who was just beginning to put her adult life in order.

Just a few months before she died, Sasha Hedgecock had been baptized in the Pecos River in front of 30 friends and family. She’d been a member of two churches in town, including Oasis Christian Fellowship, where hundreds of friends, family, and sympathetic strangers attended the young woman’s funeral in early January 2003. With her churches, Sasha had participated in several mission trips, volunteering with youth groups in Mexico and Texas.

Carlsbad Current-Argus, January 1, 2003

Her sisters—Desirae, Kayla, and Sierra—did what they could to process the incomprehensible loss of the family’s eldest sister, but the shock was nearly unbearable.

“They’re not handling it real well,” Carol said in the days after her daughter’s death. “She loved them so much.” Sierra, the youngest sister, had been so close to Sasha that her death resembled the loss of a parent.

Just as distraught was Zack Downen, Sasha’s boyfriend of several years, and recent fiancé. Zack had met Sasha while visiting from Dallas. They began dating, and soon after, he moved to Carlsbad to be with Sasha.

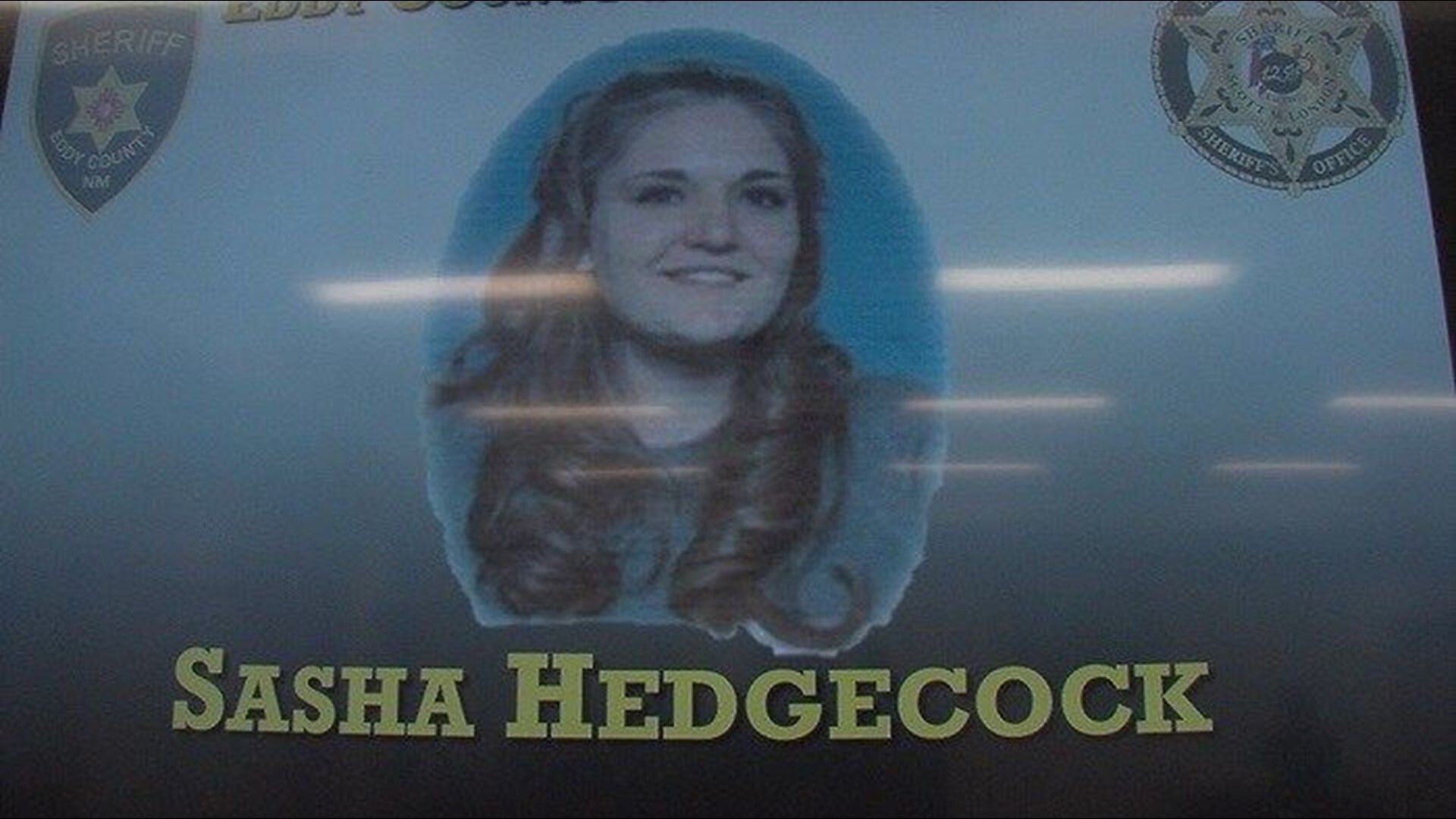

Source: Eddy County Sheriff’s Department

According to Zack, the couple planned to marry in Carlsbad and eventually move to Portales, where Sasha wanted to transfer to Eastern New Mexico University. She’d been attending New Mexico State University-Carlsbad but wanted to change schools to pursue her interest in forensic science.

Despite Carlsbad’s rough edges—the city was more utilitarian than artistic and quirky, like other New Mexico towns—Sasha and Zack had worked to build an adventurous life together.

They’d become certified scuba divers at Balmorhea State Park, where instructors teach in a dreamy, one-acre pool fed by San Solomon Springs waters that never dip below 72 degrees. In Portales, they’d planned a life centered around the university and the slower-paced lands north of Carlsbad.

Balmorhea State Park. Source: Wikimedia Commons

Instead, Zack, Carol, and her daughters were now consumed with figuring out who killed the young woman who was their partner, daughter, sister. Bill Runkle, Carol’s long-time partner and Sasha’s stepfather, was also devastated by the loss of the woman he viewed as his own child. So too was John Hedgecock, Sasha’s father, though he was in prison at the time of her death. It wouldn’t be until his release several years later that he admitted, “it really hit me.”

Together, the family sought answers to Sasha’s death, but this proved complicated. Despite her deeply religious upbringing, Sasha’s life had shadows of its own.

She had plans for a bright future, but just a few months before she was killed, Sasha was arrested for “battery upon a household member,” a charge to which she pleaded no contest. Instead of jail time, she was placed on unsupervised probation.

In the days following Sasha’s death, rumors circulated through the small town that it was drug-related—perhaps a deal gone wrong. Carol vehemently denied the rumors, but they spread quickly all the same.

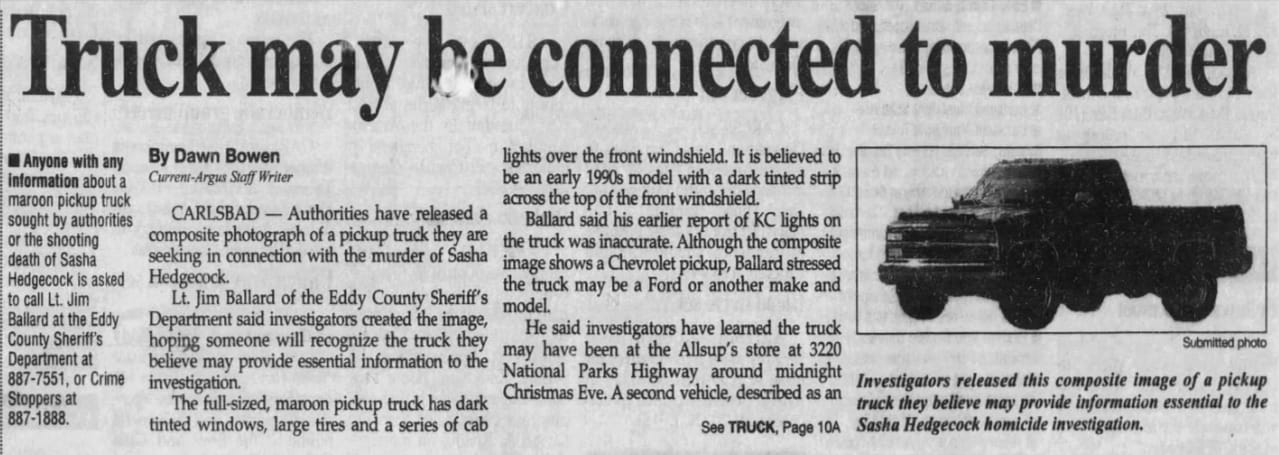

In early January, Sheriff Waller and Lt. Ballard asked the public for help identifying two pickup trucks seen at Allsup’s around the time Sasha was there on Christmas Eve. They believed one was a dark maroon, four-wheel drive pickup with heavily tinted windows. The other was black or dark blue.

Carlsbad Current-Argus, January 19, 2003

The descriptions were hardly unique in a place like Carlsbad, where industrial work was common and many locals drove big, desert-hardened vehicles. Still, it was the best authorities had to work with. They eventually released a composite photo of the maroon truck they were most interested in, and slowly worked their way through a list of registered trucks in the area.

“If you own a truck and you are contacted by police,” said Lt. Ballard, “please be patient and understanding.”

When the early days of the investigation yielded few substantial leads, the sheriff’s department openly acknowledged that residents had information about the case, but weren’t coming forward. In the Carlsbad Current-Argus, a religious group ran ads to encourage spiritual answers. “Calling the Christian community for prayer and fasting for Sasha Hedgecock’s murder to be solved,” read one bulletin.

Law-abiding residents were also rattled by Sasha’s death and other recent crimes in town. Carlsbad had experienced seven armed robberies in less than one month before Sasha’s murder, which prompted the formation of Concerned Citizens of Carlsbad, run by a local named Clifford Stroud.

Carlsbad Current-Argus, January 11, 2003

To support law enforcement, the group organized more than $15,000 in pledges toward a reward leading to an arrest and charges in Sasha’s case—or in any of the armed robberies that preceded it.

The group partnered with Eddy County Crime Stoppers, and together they ran newspaper notices whenever another significant crime occurred in town. For years, each time the Concerned Citizens of Carlsbad announced a crime, they included Sasha Hedgecock’s story—it was their origin as a coalition, but it was also a way to ensure that Sasha’s name didn’t leave the local media spotlight.

In February 2003, the Lubbock County Medical Examiner’s Office revealed the full extent of Sasha’s injuries. According to her autopsy report, Sasha had seven gunshot entrance wounds, and more than one was on her head. Additional bullet fragments removed from her body during the autopsy were placed into evidence alongside those collected during surgery the day she was found.

According to the medical examiner, Sasha also had cuts and bruises on her face, right arm, left leg, and feet. A toxicology report revealed traces of benzodiazepines in her system. A vaginal swab contained male DNA, suggesting she had been sexually assaulted.

Eddy County authorities were still waiting on results from the state crime lab, which was experiencing lengthy delays. By early April, investigators revealed they’d narrowed the scope of their case from four or five areas of interest into one key direction. That didn’t mean a suspect quite yet, they noted, but progress was mounting behind the scenes.

By the summer 2003, two investigators were working the now six-month-old case. They’d acquired several firearms suspected of being involved in Sasha’s death, but ballistics reports would take months to provide any insights into who killed the young Carlsbad woman.

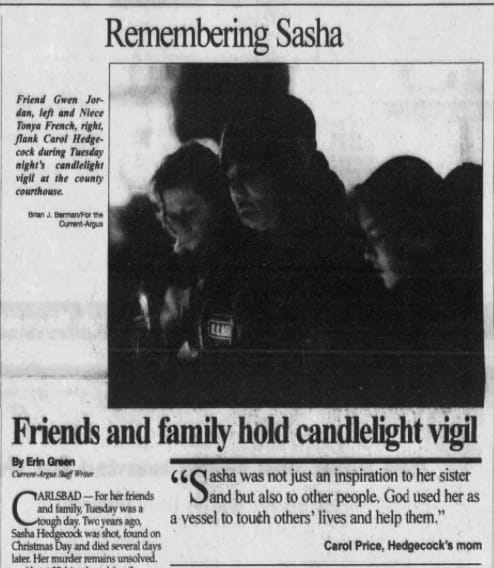

On the night of December 29, 2003, a group of Sasha’s friends and family gathered on the lawn of Eddy County’s courthouse, wrapped in blankets and winter jackets. The cold, quiet vigil marked the first anniversary of her death. In the year since, investigators were no closer to discovering who had killed Sasha, or why.

The vigil also paid tribute to other Carlsbad homicide victims that year, including 22-year-old Katie Sepich, and 37-year-old Elisa Galindo. Katie had been assaulted, strangled, and found in a landfill that summer. Elisa was killed in what was thought to be a gang-related shooting.

For Carol and her daughters, December vigils became routine. For years, they gathered in small groups to remember Sasha and pray for answers. With every vigil, other homicide victims were included in their thoughts. By December 2004, Carol’s strength was wearing thin.

Carlsbad Current-Argus, December 29, 2004

“I do have faith in the Lord that next year we won’t have to be here like this,” she said. “I am hopeful that the person who did this will be brought to justice.”

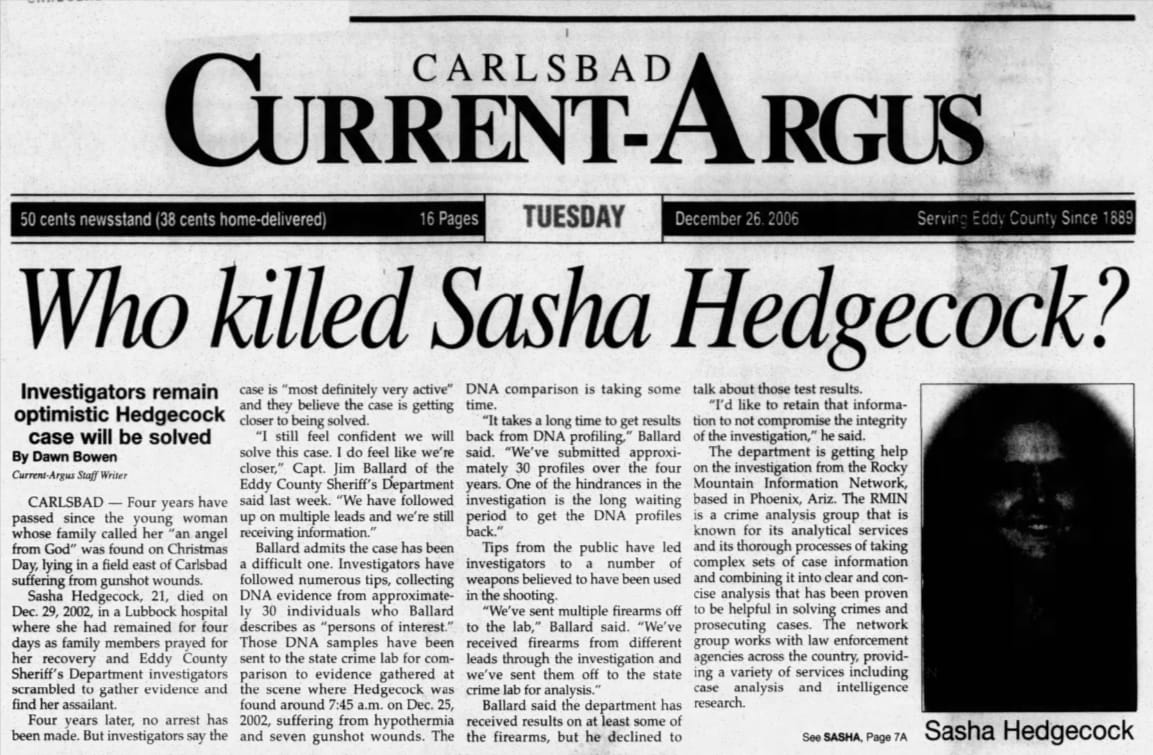

Four years after Sasha’s death, her family struggled to understand why there hadn’t been more progress in the case. “This is a small town and it’s been four years,” Carol told the Carlsbad Current-Argus. “They should have found something out by now.”

Still on the case was Jim Ballard. He’d been promoted to Captain within Eddy County Sheriff’s Department and sympathized with the Hedgecock family. But he also noted that they had worked diligently to find Sasha’s killer.

Carlsbad Current-Argus, December 26, 2006

The department had collected DNA samples from at least 30 persons of interest in the case, and was continually awaiting delayed crime lab results on various pieces of evidence gathered over the years.

Ballard and his team also received assistance from Rocky Mountain Information Network, or RMIN, a group that offered advanced crime analysis support for agencies that couldn’t solve cases through traditional means.

According to Ballard, investigators believed Sasha knew her assailants—who may have been involved in Carlsbad’s drug scene—but wasn’t herself involved in a drug deal. Their working theory was that Sasha had a “conflict” with this person that ultimately led to her being found in the alfalfa field on Christmas Day.

Ballard and Lt. Jeff Zuniga believed the key to the case was still, as it had been in 2002, someone coming forward with information. “I just wonder what they would want someone to do if this was their child,” Zuniga said in December 2006.

Carlsbad Current-Argus, November 22, 2006

For years, every time the Carlsbad Current-Argus ran a Crime Stopper Crime of the Week, Sasha Hedgecock’s story served as its tragic boilerplate. For a time, her unsolved murder became part of the town’s criminal identity.

On the morning of August 31, 2003, six months after Sasha’s death, a couple practicing target shooting at an old dump site east of Las Cruces discovered the lifeless body of 22-year-old Katie Sepich. She had been assaulted, strangled, and burned in what investigators believed was an attempt to cover the crime.

Katie had grown up in Carlsbad, about 160 miles east of Las Cruces, and had recently graduated from New Mexico State University. In late August, she was celebrating the end of summer with her boyfriend and friends, and preparing to start her MBA program at NMSU.

Katie Sepich. Source: Las Cruces Sun News

The night before she was found dead, Katie had gone to a party with friends about two miles from where her body was later discovered. After a fight with her boyfriend, Katie left the party in a hurry, without her keys, purse, or cell phone. She made the five-block walk home, but as she was getting inside, Katie was brutally attacked by an unknown assailant.

DNA evidence was recovered from Katie’s body—skin beneath her fingernails—just as it had been from Sasha’s body six months earlier. The DNA sample was processed and uploaded to CODIS, the FBI’s nationwide forensic database. But the DNA didn’t match anyone in the system, and it would take nearly four years for Katie’s assailant to be discovered and charged.

In November 2003, less than three months after Katie’s death, a man named Gabriel Avila was arrested for breaking into the apartment of two young women in Las Cruces. The roommates barricaded themselves in a bedroom to avoid Avila, who was eventually caught, arrested, and in March 2004, convicted of aggravated burglary.

After being released on bond, Avila fled to avoid his nine-year sentence, and remained at large until November 2004. Upon entering the prison system as a convicted felon, Avila gave a DNA sample, a routine procedure under New Mexico state law. It sat untested for two years. When it was finally analyzed, it matched the DNA recovered from beneath Katie Sepich’s fingernails in 2003.

In 2006, with evidence stacked against him, Avila confessed to Katie’s murder. To avoid the death sentence, he pleaded guilty to first-degree murder, rape, kidnapping, and tampering with evidence. Avila received a 69-year prison sentence.

Katie’s case was solved in less than four years, but her parents, Dave and Jayann, believed it could have concluded much sooner if New Mexico had made one significant change to its DNA policies. Instead of collecting DNA samples only after felony convictions, what if the state mandated that samples be taken for any felony arrest?

In their minds, Avila could have submitted his DNA just months after Katie’s death—following his November 2003 arrest—instead of years later. By focusing on DNA collection at arrest rather than conviction, Dave and Jayann argued, the state could prevent countless crimes committed by repeat offenders.

The state of New Mexico agreed. On January 1, 2007, Katie’s Law, which mandated DNA collection upon any felony arrest, went into effect. The Sepich family then took their campaign nationwide.

Carlsbad Current-Argus, January 2, 2007

When the Katie Sepich Enhanced DNA Collection Act of 2010 passed, it provided financial incentives for states to collect DNA samples at the arrest stage for “crimes involving murder, manslaughter, sexual assaults, and kidnapping or abduction.”

The Sepich family’s steadfast efforts to change New Mexico’s DNA policies would, in the coming years, help solve countless cases by matching DNA samples to evidence collected at crime scenes around the state.

One of those cases would be Sasha Hedgecock’s.

In 2009, a man named Jeremy J. Melendrez was arrested for a series of violent crimes in New Mexico. He was charged with, among other things, aggravated burglary with a deadly weapon, aggravated battery, and conspiracy to commit aggravated burglary.

By then, Katie’s Law had been in place for several years, so when Melendrez was arrested, the state collected and uploaded his DNA to CODIS. In 2010, he was convicted and sentenced to six years in prison.

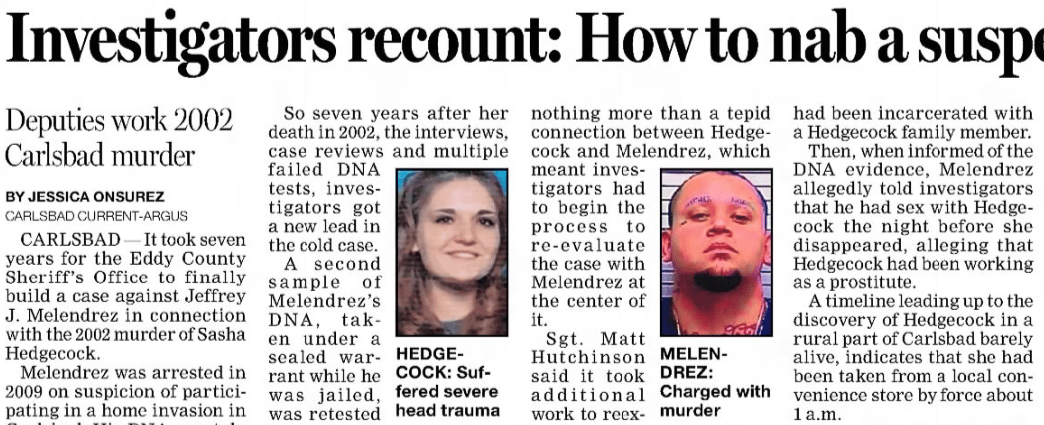

Seven years after his arrest, in April 2016, Undersheriff Chief Mark Cage announced that Eddy County finally had a suspect in the murder of Sasha Hedgecock. It had taken more than a decade, but the connection between Melendrez and Sasha was finally and firmly established.

Albuquerque Journal, April 24, 2016

Sadly, Carol Price had passed away in 2013 and never saw her daughter’s case resolved. For Sasha’s sisters and the Sepich family, the arrest was a step toward resolution and proof that Katie’s Law was helping authorities solve longstanding cases.

“We are very, very happy that Katie’s Law could play a role in this,” Jayann Sepich said, “but that just provided a lead that they had to take, and they had to investigate, and had to go out and make a case. And the District Attorney had to say ‘Yes, we’re going to prosecute this case.’”

Melendrez, who was not cooperative with Eddy County’s investigation, was charged with an “open count” of murder, which allowed a preliminary hearing to later determine the specific degree of the charge. Melendrez had been scheduled for release from prison in 2016, but the new charge meant he would continue to be held at GEO Prison in Hobbs, near the Texas border.

For investigators, it took seven years to build a strong case against Melendrez. Even with the suspect’s DNA evidence collected in 2010, Eddy County Sheriff’s Office detectives had to review old interviews, evidence, and original files to ensure they had a case that would stand up in court.

In the early days of their focus on Melendrez, he denied knowing Sasha at all. Later, Sgt. Jeff Zuniga and his partners uncovered a “tepid” relationship between the two. Finally, when faced with the DNA evidence found on Sasha’s body, Melendrez concocted a story about the night of December 24, 2002, that didn’t fit anything else in her case file.

In his version of events, Melendrez met Sasha at a known “drug house” in town, then proceeded to have consensual sex with the young woman, who he believed was working as a prostitute.

Afterward, he claimed he was threatened by two men he thought worked with Sasha. Melendrez didn’t know how she ended up in the alfalfa field, suffering from hypothermia and multiple gunshot wounds, he claimed. No other testimonies in the investigation supported anything Melendrez told detectives.

“Mr. Melendrez provides us a story,” said Sgt. Matt Hutchinson, “and then that’s where we begin to start to poke holes in that story. Just that process it takes a matter of time to be able to get all the pieces in place to write a complaint.”

When shown a missing-persons flyer with Sasha’s photo during one interview, Melendrez became “visibly upset,” investigators noted. “He continually stared at the flyer, chewed his lip, and stopped making eye contact with the investigators,” read the interview transcript.

The effort to wade through Melendrez’s stories, however frustrating, paid off in an unexpected way. He hadn’t been among the 30 or so suspects who gave DNA samples back in 2003. Without his unrelated arrest and the genetic database hit years later, thanks to Katie’s Law, Melendrez might never have surfaced as a suspect.

In March 2017, after discussing their options with Sasha’s family, prosecutors announced they would not seek the death penalty for Melendrez. The open count of murder was upgraded to first-degree murder. If convicted, the defendant could face life in prison.

In February 2018, Melendrez announced to Carlsbad’s Fifth Judicial Circuit Court that he would be entering an Alford plea to voluntary manslaughter. This type of plea deal allows a defendant to maintain their innocence while acknowledging that the case against them is likely strong enough to establish guilt in a jury trial.

“After an overall assessment, meeting with the Hedgecock family, and based on the strength of the case,” said District Attorney Dianna Luce, “we made a decision to make an offer.”

By February 2018, Melendrez had already served nearly two years on the charge, with an estimated three more years remaining under his plea agreement, which carried a maximum of six years in prison.

For the Hedgecock family, the plea agreement marked the legal resolution of Sasha’s case. But justice on paper hardly brought closure to Desirae, Kayla, Sierra, or Sasha’s friends and community.

Melendrez’s story didn’t end with his plea in Sasha’s murder. By May 2021, out on parole, he faced new charges for criminal property damage and probation violations. Those charges were eventually dismissed, but by June 2023, he was wanted again, this time for two separate violent incidents in Carlsbad.

In one, a woman at Friendship Park was found shot in the head. She survived, and recounted to police that two men had appeared to be arguing at the park. She’d heard two shots fired and remembered little afterward. She didn’t identify Melendrez specifically, but authorities believed he may have been involved in the shooting.

In another incident, on the same day, a man was stabbed several times in the head before neighbors forced the attacker to flee. One witness later identified the assailant as Melendrez, and claimed he was armed when he left.

Throughout the summer of 2023, Melendrez allegedly committed a series of crimes—including the robbery of an Albuquerque Pizza Hut—and in September 2023, he was arrested after an hours-long standoff with Carlsbad’s SWAT team.

“It’s not like he was having a bad day,” said Captain Jessie Rodriguez of the Carlsbad Police Department. “This individual has been involved in multiple incidents throughout the course of his life where he’s put people in danger or caused injury.”

Today, at least 25 states have passed some variation of Katie’s Law, requiring or incentivizing expanded DNA collection for arrests in violent crimes. Since 2007, New Mexico alone has matched DNA from more than 1,500 felony arrestees to hundreds of cold cases, including Sasha Hedgecock’s.

Sasha never reached Eastern New Mexico University to study forensic science, or to live with her fiancé Zack. Instead, her story became a tragic part of the field she'd hoped to one day enter, an enduring link to the advocacy that began in New Mexico and transformed DNA collection nationwide.

• • •